Think back to your grade school history class when we learned about a couple of adventurous French traders and explorers affectionately called “Radishes and Gooseberries”. Pierre-Esprit Radisson and his brother-in-law Medard des Groseilliers lost faith in France’s royal court and potential financiers, which resulted in them leaving their countrymen and offering their services and first-hand knowledge of North America’s bountiful fur reserves to King Charles II of England. On May 9, 1670, a royal charter was granted to the Governor and Company of Adventurers trading into Hudson’s Bay and the Hudson’s Bay Company was formed. All waters flowing into the Hudson’s Bay were included in this grant which included the Moose and Missinabi River basins which Radisson learned could be accessed through Michipicoten and Lake Superior. Life in North America would never be the same again.

The birth and evolution of the fur trade could not have been achieved without the guidance, trust and knowledge of the Indigeneous Peoples of North America. Cooperation with the well-established social, economic and political cultures in this “New World” became invaluable to the trading of goods for furs to meet European fashion demands. The Indigenous Peoples shared their knowledge of the land, the food, the travel routes and the furs. The men were the backbone and labour – sharing their skills for making and using the tools of the trade (canoes, snowshoes, traps etc.) as well as paddling and portaging mountains of goods and furs in and out of the deepest interior of the continent. The women provided the foundation and essentials of life – preparation of both food and furs, maintaining the home and hearth, and offering timeless knowledge of plants and seasons for medicines, nutrition and vital tools and items for daily survival. Many women married company men and their descendants evolved into a vibrant and unique culture known as the Metis.

I learned about the Hudson’s Bay Company long before my grade school history teacher had the chance to introduce me to our required Canadian history curriculum. My grandmother often shared stories of provincial archaeologists visiting our family cottage near the mouth of the Michipicoten River. Over the years interesting artifacts and items would appear in the rusty waters of the Michipicoten, carried downstream from a series of fur trading posts dating back to the early 1700’s. A variety of archaeological digs in the late 1960’s and early 70’s resulted in a number of large collections of both pre-historic and historic “Michipicoten” artifacts currently archived, stored and displayed in a variety of museums and universities throughout Canada.

The Hudson’s Bay Company built a post at Michipicoten in 1797. The first factor (boss) for the Michipicoten Post was Henry John Moze who arrived at Michipicoten on June 8, 1797 after paddling from Moose Factory and waiting 11 days at Missinabi for the lake ice to thaw. Moze was accompanied by his “Indian Guide” and three company men to assist in carrying goods and help in building the new post. The choicest location for a post at Michipicoten however was already taken by the HBCo’s main rival, the North West Company. It’s a long story, but suffice it to say, both companies could not compete and in 1821 the two amalgamated as one under the banner of the HBCo. Due to Michipicoten’s strategic location on the East/West trade route through Lake Superior-Georgian Bay-French River to Montreal, AND the North/South route from Lake Superior to James Bay, the HBCo established their Lake Superior District Headquarters at Michipicoten from 1821 to 1887.

As a result of the location of the HBCo. Post, Michipicoten was the centre of activity. Local Indigenous residents who at one time roamed the land with the seasons and food sources, began to set up permanent residence near the Post complex on the banks of the Michipicoten River where it meets the Magpie. Michipicoten River Village can trace its perpetual roots well back into the 18th century. Indigenous seasonal occupation in the vicinity has been scientifically dated 2000 years before present.

Interactions between Michipicoten’s earliest residents and the HBCo. did not always benefit both parties. Common ailments and viruses easily fended off by the employees of European descent had devastating impacts on the North American’s physiology. William Teddy and Louis Towab’s family lost 7 children in an epidemic in 1895-96.

Much of the focus and objective of the trading empire was to ensure the local trappers became dependent on the goods and items traded. These not only included items to ease daily existence, but also items which would have devastating effects on the social and economic character of North American cultures. Guns changed the political boundaries, power centres and strategic rivalries. Alcohol and its chronic ailments had devastating effects on individuals, families and entire communities dependent on each other to survive in a harsh and fragile landscape where starvation was not uncommon.

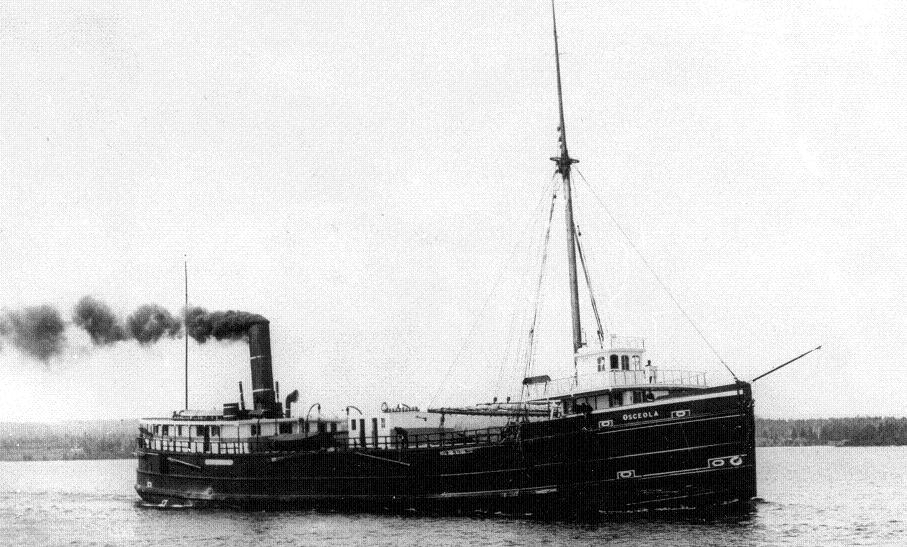

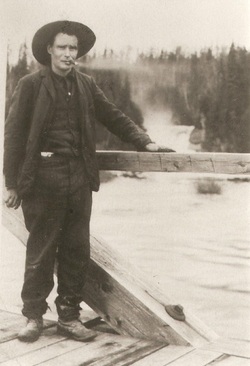

Over harvesting of local beaver and other fur-bearing mammals in the mid-1800’s meant Michipicoten needed to diversify to ensure the post could cover expenses. Post employees became proficient fishermen, netting seasonal stocks of sturgeon, trout, herring, whitefish and pike. Fish would be salted, packed in barrels and shipped to southern markets. Michipicoten had a productive tinsmith and blacksmith shop. Post employees also built wooden York boats to replace the more fragile birch bark canoe. The post was utilized by travelling missionaries for sermons, baptisms, and marriages. Indian agents also made annual visits to provide the annuities to Michipicoten First Nation members after the signing of the Robinson-Superior Treaty of 1850. Michipicoten also operated as a post office and the first Mining Divisional Office of Ontario in 1898 after the discovery of gold on Wawa Lake in 1897 by William Teddy and Louise Towab.

Amenities at the Michipicoten HBCo post provided travelers not only supplies and a warm meal, but also a respite from sleeping in tents and out in the elements during long stretches of paddling on Superior and the Michipicoten River. These guests and travelers included a long list of characters we learned about in that same grade school history class: Sir Sanford Fleming, Alexander Mackenzie, Frances Ann Hopkins, David Thompson, Louis Agassiz, Governor George Simpson, to name just a few.

Although the post was instrumental in providing supplies, provisions and prospecting licenses to the rush of miners seeking their fortune in gold in 1898-99, Michipicoten was unable to compete with trading posts in the Chapleau area next to the Canadian Pacific Railway. In 1904 the HBCo eventually closed the Michipicoten Post.

The HBCo. renewed its presence in Wawa when The Bay Department store opened its doors on Broadway Avenue in the early 1960’s. The Bay was an integral part of the downtown business sector even when it was rebranded as the Northern Store and later sold to the Northwest Company. Almost like the story came full circle.

The Bay is no longer a fixture in Wawa, and the HBCo. is no longer a Canadian company. Even with American proprietors, the HBCo blankets, signature colours and cast of characters continue to represent a truly Canadian story that reflects our adventurous spirit and links with the incredible landscape we call home. Wawa should be proud of the ties and strong connections it has to the people, communities and cultures which are woven into 350 years of the unique Hudson’s Bay Company story.

To discover more information about Michipicoten’s rich history, you can explore the Canadian Museum of History website for the "Michipicoten Pot" or go to the Royal Ontario Museum website and search the online collection for a painting of the Michipicoten Post completed in 1897 by William Armstrong.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed